Inside Game no. 7: Mike Morin

Our Man in the Trenches

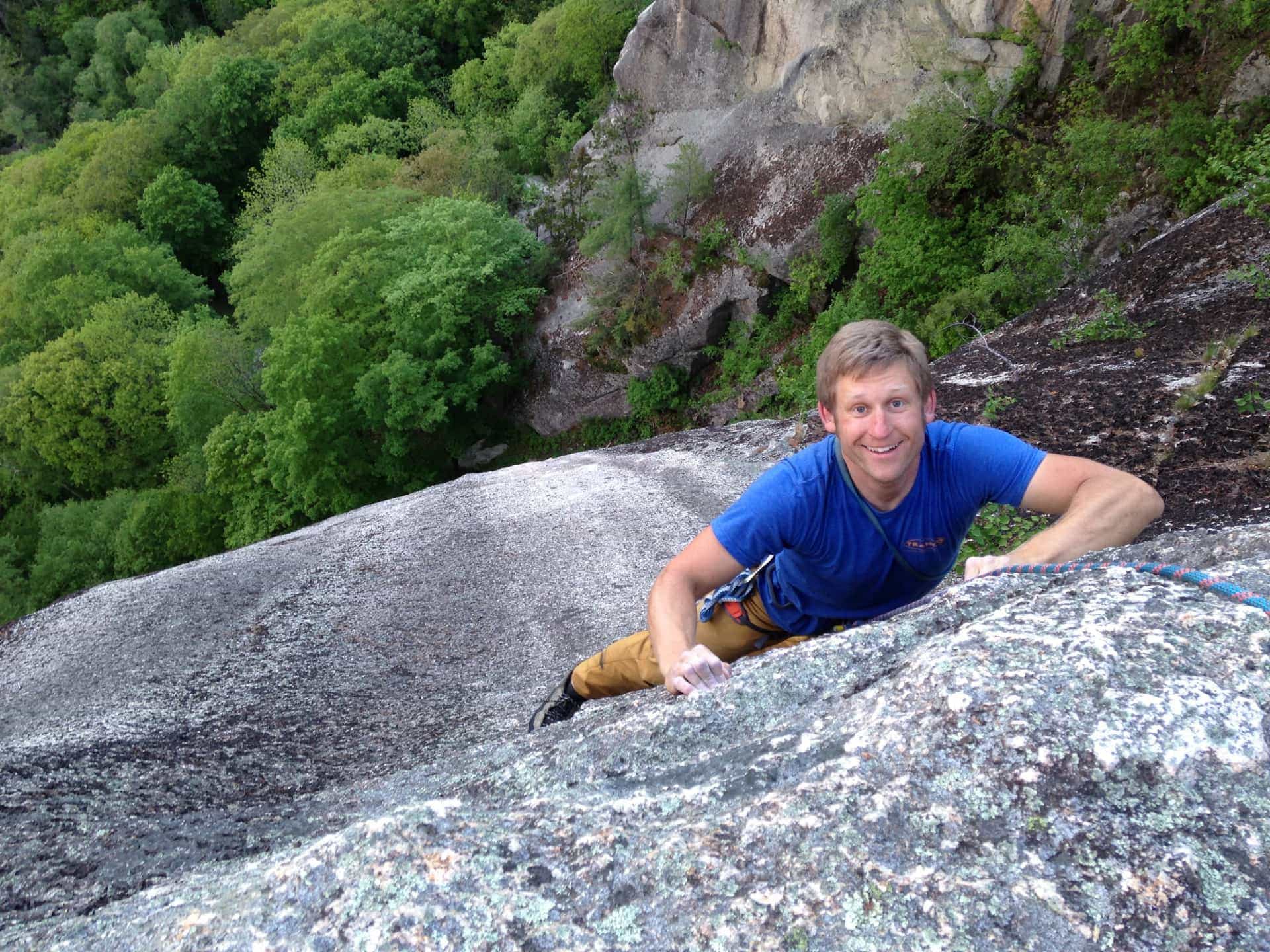

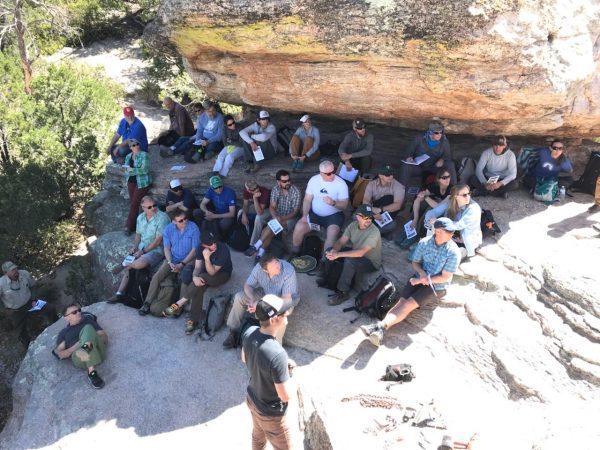

“It’s funny, people’s idea about what a bolt or fixed protection is,” says Mike Morin, the Access Fund’s Northeast Regional Director. “If you’re not a climber, ‘bolting’ can sound so ominous. A big part of my job is to explain and break down those barriers.” A self-described access “nerd”, Morin recently gave a hands-on bolting demonstration to a group of National Parks Service rangers and land managers gathered in Tuscon, Arizona, for wilderness climbing management training. First, he demonstrated the use of a power drill. Then, he demonstrated the old-school hand drill method. “Once I started tapping the drill with a hammer, everyone was like, ‘really? This isn’t a big deal. It’s obviously not threatening to wilderness…’”

Mike Morin is a familiar face to Salt Pump climbers, and a native Mainer. He was born and raised in Bradley, a little town of 1,500 people across the river from Bangor in Penobscot County. His first memorable outdoors experience was catching a yellow perch with his grandfather from Dolby Flowage. From there, his outdoor career progressed into mountain biking, hunting… and more fishing. Morin went to the University of Maine in Orono, where he majored in Parks & Recreation & Tourism.

“In college, I went climbing in Acadia, but I really didn’t pursue it until I moved west and started mountaineering in Colorado,” he recalls. “I met a good friend and started to go out rock climbing in the Front Range, and got hooked.”

Morin worked for nine years as a park ranger and recreation manager in Colorado and Maine before he transitioned to the Access Fund. In three years, he and his wife Amanda lapped the country three times as a traveling conservation team, leading efforts to build sustainable climbing trails and educating climbers and land managers about best practices for conservation.

Last year, Mike’s climbing journey took him full circle, back to his New England outdoor roots when he moved to North Conway, New Hampshire to lead the Access Fund’s regional initiatives. His mission? To keep climbing areas open and conserved. We caught up to him to learn more about his work and the future of New England’s crags.

How has your first year back in New England been?

It’s just awesome being back in the Northeast… Amanda and I discovered the Mount Washington Valley late in life – growing up in Maine, we didn’t come down here – but I started coming here when I was traveling for the Access Fund. We got exposed to how great the White Mountains are, and North Conway was on our short list of places to settle down.

“This is hard work.” Mike showing a group of National Park Service land managers how to hand drill a bolt.

How are the access issues in New England different from what’s going on out west?

The big thing here is all the private land – we don’t have big tracts of federally protected, wild land compared to out west, so a big part of my job is working with local land managers and private owners. And, a lot of our climbing areas are really old – people have been climbing in the Appalachian chain for almost a century. There’s a lot of history.

With private land, it’s all about sitting at somebody’s kitchen table and understanding their concerns, then figuring out what can be done. With the local land managers – state land, or a town forest, or a private land trust – it’s different from Federal land, which often has a mandate for public involvement. For instance, there’s usually a public comment period when a new management plan come out. Locally managed public land doesn’t always have that process, so you have to be more proactive.

What’s the current status with bouldering at Bradbury Mountain?

We’re trying to engage with the local land owners – most of the bouldering is on private land adjacent to the state park. What happened is, the previous land owners sold the land, and the new land owners pretty much immediately closed it to all recreational access, citing concerns around impact. This is a prime example of a typical access issue in this region. They don’t have to talk to us. It’s their land. We’ve reached out to them in an effort to just start a dialogue, find out more about their concerns, and so far – unfortunately – they have refused to meet with us.

Our initial outreach was we sent a letter, from the Access Fund, Evo and Salt Pump, and then we tried to work some local angles… It’s still very much on my radar and we’re working hard to find a personal connection with the land owners that will help spark a productive conversation.

The Access Fund is in it for the long game so we’ll keep trying to reach out and hopefully we can do what it takes.

A professional crew of trail-builders from the Access Fund recently completed this stone staircase near the start of Recompense on Cathedral Ledge.

The Access Fund does work on the local, regional, and national level. What’s going on in Washington, D.C.?

AF’s Policy team is constantly engaged with lawmakers and administrators Washington D.C., but along with that, every year staff and volunteers from around the U.S. go down to D.C, with a set of issues that we’re trying to lobby for and bring awareness of to lawmakers. This year, my team talked to New England representatives about the ‘Recreation Not Red Tape’ bill – this would streamline permitting for guides who want to guide on federal land. We also lobbied for ongoing support and protection of the Antiquities Act, which allowed for the designation of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument and Bear’s Ears National Monument. We also lobbied for full funding of the Land and Water Conservation Fund which provides funding for the purchash of land and other recreation and conservation projects… It used to be something that got bi-partisan support, but unfortunately, it’s become political. It’s funded by offshore oil and gas, not citizen taxes, and has been around since 1965.

When discussing the importance of the Antiquities Act, and the Land and Water Conservation Fund I tried to make the point to our representatives that with shifting values, and concerns over liability leading more and more private land owners to close their property to recreation, maintaining the ability to enhance protections on existing federally managed public land, and fund new acquisitions for public land and spaces is becoming only more important.

What are the things people in the Maine climbing community can do to get involved?

I would love to see a grassroots climbing group based in southern Maine… It would be great to have a local organization to help us tackle issues like Bradbury. A lot of the time, grassroots groups don’t form until there’s a pressing issue – but it’s best to be proactive and organize before you need to. We have 121 local climbing organizations we work with nationally, including the Clifton Climbing Alliance, but there’s not one focused on southern and western Maine. I think there’s definitely an opportunity. In local issues, there’s nothing more powerful or effective than a group of concerned citizens advocating for themselves.

Any personal climbing or adventuring goals for this year?

I want to spend a week up at Katahdin this August. But really, I’m enjoying being a bit of a homebody these days. I travel a lot for work, so being home is nice. It was an important consideration moving here… all the adventure I need is right here.